Maternal Health Equity in America

We, as Black women, are successful in many disciplines, and yet we remain one of the few demographic groups who must tirelessly advocate for appropriate care. When will it be our turn for access to consistent, high-quality health care?

While there have been substantial advances in health care, there are a host of social and economic inequities that affect our health outcomes. Even though we’ve seen developments in everything from cancer to HIV research, diabetes, mental health, and hunger to homelessness and LBGQT+ issues, maternal and maternal morbidity continue to persist. Medical research suggests that these poor outcomes directly correlate to social-cultural issues, requiring intervention and prevention efforts to address critically.

Black women already have a shorter life expectancy due to chronic conditions like anemia, cardiovascular disease, and obesity than other women in the United States. Despite knowing much of the causation of those issues, it is not immediately clear why we experience higher rates of maternal mortality than other races and die at higher rates than women in many third-world countries.

Contemporary discussions suggest that maternal morbidity and mortality are contributed by the intersection between race, gender, and discrimination and are not simply explained by a woman’s education or income. Discussion findings reveal that chronic conditions of maternal morbidity and mortality are historical in nature and reflect inequities within and outside the health system Black women experience throughout their lives. These structural inequities were in place for Black women before they were physically able to birth a child. In other words, the educational, environmental and family systems influenced the health wellness and awareness of black women before childbearing years all of which play a part in the outcomes of maternal morbidity and mortality.

There are increasing and persistent negative maternal mortality and morbidity outcomes at every educational level for Black women. We are nearly four times as likely to die while pregnant or within one-year postpartum when compared to our white and Latina counterparts. Additional risk factors that cause us to have severe maternal morbidity and mortality are hemorrhage, infection [sepsis], thrombotic pulmonary/other embolisms, and pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders. Other known contributing factors are the quality of care, and giving birth in hospitals with frequent, severe maternal morbidity rates or low-performing hospitals with poor patient-provider prenatal and postpartum communication.

Understanding Mortality Rates in Black Women

As previously stated, research suggests maternal morbidity and mortality collide at the intersection of race, gender, and discrimination regardless of education or income levels.

Structural oppressive systems result in unfavorable social-economic conditions like high rates of unemployment, poverty, and poor housing.

The following table illustrates some alarming facts that influence maternal mortality and morbidity outcomes for Black women:

| Table 1: Demographic for U.S. Black Women, 2018 | Black Women | All Women |

| Percentage of population | 7.0 | 51.5 |

| Percentage of women | 13.6 | 100.0 |

| Mean age (years) | 36.1 | 39.6 |

| Percentage currently married | 26.0 | 46.0 |

| Percentage educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school | 13 | 11 |

| High school | 29 | 26 |

| Greater than high school | 58 | 63 |

| Percentage poverty | 24 | 14 |

| Percentage owner-occupied housing | 41.4 | 63.9 |

| Percentage head of household | 27 | 12 |

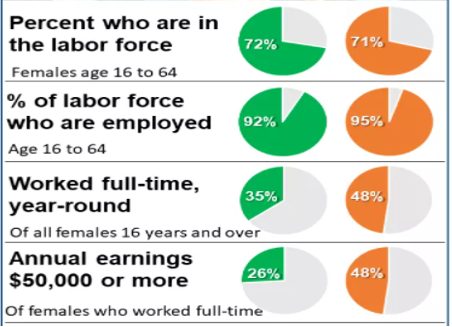

Typically, as the head of household, we have fewer resources, more dependents, and are more likely to live in poverty-stricken neighborhoods where we’re exposed to lower property values and environmental injustices. In fact, on average, Black women make approximately $6,000 less per year than white women and are more likely to experience unemployment.

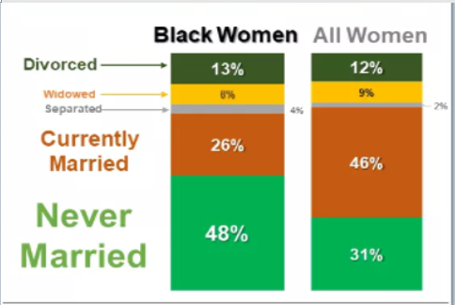

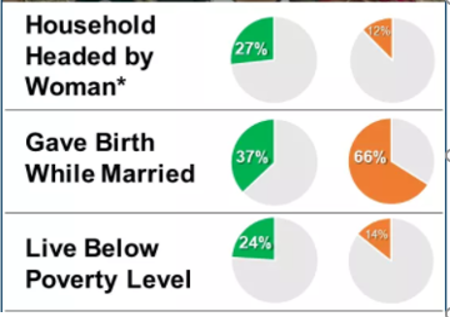

Tables 2A-2C illustrate a sampling of the social outcomes we face as Black women. They demonstrate the profound impact that race and inequity have on our well-being.

Table 2A: Women and Relationships 15 years and older

Table 2B: Head of Household Comparison of Black Women and All Women

Table 2C: Comparison of Black Women and All Women in the Workforce

Know Your Health Risks

Obesity

Because there is a high prevalence of obesity among Black women, we also have higher rates of weight-related health issues, including stroke and cardiovascular diseases. In fact, those who identify as Black have more incidences of obesity than any other racial/ethnic group. We also tend to have a more positive body self-image, which is believed to also reduce our motivation to lose weight. This is critical because the high prevalence of obesity among Black women influences high rates of stroke and cardiovascular diseases that directly influence maternal mortality and morbidity.

Cardiovascular Disease

Although cardiovascular diseases have declined overall, Black women continue to experience higher rates of cardiovascular mortality when compared to white women. Causation is linked to poorer heart health and a higher burden of clinical and behavioral risk factors, which starts to decline in younger years. These factors have significant implications for maternal and infant health.

There are also inherent biological and social constructs drivers we face beyond our control like genetics, epigenetics, and individual, interpersonal, and community influences.

We can control the behavioral factors that lead to CVD. We decide our diet, physical activity, sleeping habits, alcohol use, if we smoke, and we have the ability to manage our emotional health and stress. Once we gain control in these areas and seek help when needed, we can better maintain our heart health. Behavioral factors affect Black women as early as 20 years of age including risk factors that influence health issues like obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

Sleep Disorders

Sleep disparities are an often-overlooked issue within our demographic. We’re more likely to have sleep issues — from not sleeping enough to obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, and poor sleep quality. If you’re not sleeping well, you should absolutely discuss what you’re experiencing with a doctor. Black women are less likely to report their sleep disturbances to a doctor. Among other health problems, cardiometabolic disease alone can be activated by inadequate sleep.

Blood Disorders

There are numerous diseases of the blood common to Black women, many of them ancestral, like anemia (iron deficiencies) and sickle cell anemia (SCD). Other concerns such as malignant cancers of the blood (e.g. leukemia, myeloma, and lymphomas,) are also likely to contribute as preconditions affecting maternal mortality and morbidity. Sadly, there are well-documented differences in the treatment experiences that we receive resulting in poorer outcomes than other races.

Mental Health

It’s a topic that doesn’t get discussed nearly enough in our community. It also doesn’t get researched enough. There is far too little known about our behavioral health risks — including suicide attempts/occurrences, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse — and their correlation to race, gender, maternal mortality, and morbidity. Moreover, our mental health is continuously impacted by racial discrimination, which is a toxic, unpredictable stressor that contributes to poor physical and psychological health.

When our mental health starts to negatively affect our physical and psychological health, maternal health is also impacted in a variety of ways. Where depression and anxiety already exist, prenatal care can be delayed, which often leads to an increased risk of unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Concerningly, more than a quarter of Black women in the United States are believed to experience perinatal depression, which is thought to induce preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, pre-term births, and low birth weights. Each one of those issues relates to maternal mortality and morbidity.

Even more alarming is that a leading cause of death during pregnancy and postpartum is also homicide, which remains under-studied and is typically not captured in examinations of pregnancy-related deaths or maternal mortality. Our mental health as well as those around us is critical to even begin addressing this often-overlooked crisis.

The following table illustrates alarming statistics that reveal maternal mortality and morbidity outcomes for Black women:

| Table 3: Health Statistics for Women | Non-Hispanic Black women | Non-Hispanic White women | All women |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 77.9 | 81.0 | 81.0 |

| Infant mortality | 10.9 | 4.7 | 5.8 |

| Maternal mortality | 37.1 | 14.7 | 17.4 |

| Pregnancy-related mortality | 42.4 | 13.0 | 16.9 |

| Physical health (prevalence %) | |||

| Heart disease | 9.9 | 10.8 | 10.1 |

| Hypertension | 39.9 | 25.6 | 27.7 |

| Obesity | 34.7 | 21.6 | 23.5 |

| Mental health (prevalence %) | |||

| Serious psychological distress | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Suicide per 100,000 population | 2.8 | 7.9 | 6.1 |

Data source: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jwh.2020.8868

Overcoming Barriers

The Journal of Women’s Health has done an excellent job reporting some of the unique health conditions Black women experience. The article is quick to point out a lack of current and accessible information regarding the health constraints we face, which are critical to intervention and prevention.

From limiting implicit biases that a provider may hold to acquiring more data that examines the intersectional trends between race and gender, we must find opportunities to improve maternal mortality and morbidity rates. We, as Black women, must continue to be our greatest advocates because without equity in social and economic conditions, health disparities in the lives of Black women as a collective group is unlikely to be achieved.

Further Reading

Special Issue Article: Journal of Women’s Health Vol. 30, No.2

(https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jwh.2020.8868)